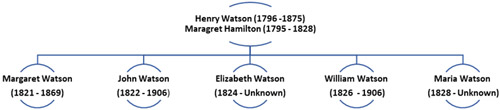

William Watson was born in 1826 in the village of Skelmorlie in Ayrshire, twenty-five miles west of Glasgow on the Firth of Clyde. His father, a landscape gardener named Henry Watson, had been born in England. He’d come to Skelmorlie in 1820 to lay out the grounds of Ashcraig, the estate of Andrew D. Campbell, a retired sugar planter. [1]

In that same year, Henry married Margaret Hamilton who it’s understood, was born in Glasgow. They went on to have 5 children together. Sadly, Margaret, died shortly after her youngest daughter, Maria, was born and when William was only two. Henry Watson remarried in April 1833, this time to a Robison McLean, an Ayrshire native, who not only took on Margaret’s five children but went on to have four children of her own with Henry. Henry remained at Ashcraig as gardener, living in the gardener’s cottage (now Ashcraig Cottage) with his family until 1854 when AD Campbell and his wife died. Thereafter they moved to Pierhead and what was to eventually become Meadow Place.[2]

Source: Skelmorlie Villas – Henry Watson and Family

After attending the local school, which would have been located at the Meigle, ¼ mile north of Ashcraig, he then trained as a ship building engineer. William, being ‘something of an adventurer’ and perhaps through the influence of his father’s employer, emigrated to Bermuda, around 1850, aged 24, where he was employed as a civil engineer and sometime ship’s captain. [2] [3] [4] [5]

In the mid-1850s he moved to Louisiana, and by 1860 was part owner of a sawmill and a coal and steamboat business in Baton Rouge. As an expert mechanic he often did repair and installation of the sugar mills and refineries of the surrounding country, and therefore came to know some of the well- known planters and politicians. [3]

To a degree, William’s sympathies lay with his adopted region. He believed the Southern planters were the real producers of the country, bearing all the hard work and deprivations whilst being hated as slaveholders, while the North, was pocketing the lion’s share of their labours, living in ease and luxury, and maintaining an exterior of virtue and sanctity. [3]

Although opposed to secession he enlisted with the Confederate Army for a year partly because he felt his personal honour, and that of Scotland, would be at risk if he did not follow the army, partly because it was in his business interests to volunteer and partly because of his love of adventure and glory.[3]

In April 1861, following the bombardment of Fort Sumter (the first military action of the American Civil War), Watson joined K Company of the 3rd Regiment of the Louisiana Infantry, nicknamed the Pelican Rifle, which comprised 86 volunteers all from the East Baton Rouge Parish. There, he was elected to the position of sergeant, by the men, who were mainly sons of planters, merchants, bankers, businessmen, professional men and students. Several times during the following year Watson was offered higher rank but refused to accept a commission as an officer, as it would require him to renounce his allegiance to Queen Victoria. [3]

In late June, the 3rd Louisiana regiment, by then 1,060 strong, was ordered to Arkansas to join McCulloch’s army of the West. On July 5, the army left Fort Smith and marched into southwest Missouri, where on August 10, 1861, the Army of the West and its ally, the Missouri State Guard, won an impressive victory at Wilson’s Creek, or Oak Hill, as the Rebels called it. [3]

Source: www.history.com/this-day-in-history /battle-of-Pea-Ridge-Elkhorn-Tavern-Arkansas

Watson’s second battle in February 1862, was at Pea Ridge, or Elkhorn Taverns as part of the confederate right wing. After enjoying early success, the regiment fell apart when McCulloch, the commanding officer, was shot dead and the Colonel was captured along with a large part of the regiment. From there, the army withdrew to Van Buren and the regiment back to the garrison at Fort Smith. After a month of regrouping and recuperating, the 3rd Louisiana evacuated Fort Smith on March 28, arriving at Memphis on April 18. From there, Watson’s regiment proceeded to Corinth by rail, arriving too late to take part in the battle of Shiloh. [3]

On May 6, 1862, Watson took part in the battle of Farmington in Mississippi, part of the Siege of Corinth, where they fell on the Union left and drove their advantage home. However according to Watson, this fight ‘was of no great proportions, and was very little noticed’. [3]

Finally, on July 19, 1862, Watson was discharged at Tupelo, Mississippi. Noted in his discharge papers was the fact that he was ‘indebted to the Confederate States by $3.25 on account of shoes.’ [3]

Baton Rouge was by this time in Union hands, but Watson sneaked through the picket line at his own “wood factory,” on the Mississippi River and after three days visiting friends, took a steamer down river to New Orleans. There he reported to the British consul, who issued him a certificate as a British subject, granting him neutral status. After being arrested for treasonable language and let off with a warning, he returned to Baton Rouge but as all of Watsons property had burned in the earlier battle of Baton Rouge, he decided the best and safest place to be was back in the army. Accordingly, Watson re-joined the 3rd Louisiana as a private, having missed in the intervening period, the battle of Luka, where the regiment had sustained 40 percent casualties. [3][4]

William Watson took part in The Battle of Corinth

On October 3, 1862, within a day of his arrival in camp, Watson took part in the (second) battle of Corinth, where he was wounded in the leg and was captured when the confederate assault collapsed. Sent to a Union field hospital, he quickly recovered and, with the assistance of a Scottish major, on General Rosecran’s staff, Watson was paroled by the US Army and upon returning to the Confederate Army, was discharged due to injury. [3][4]

Leaving the army once again, Watson made his way to West Baton Rouge Parish. In this sugar-producing region, Watson found offers of employment from planters whose levees and sugar mills needed repair. An unusually high river that autumn, however, broke through the levees and flooded the sugar country, again putting Watson out of a job. [3]

With no prospect of work in Baton Rouge, Watson ventured down to New Orleans, where he decided to get out of the country. Watson had seen service as a seaman in Scotland and the West Indies and in June 1863, secured command as well as part ownership of a small schooner, the SS Rob Roy. He made his way down the Mississippi and out of the Confederacy to become a blockade runner between Galveston, Havana, Belize, and Matamoros. [3]

Due to the war, cotton prices had soared, and extraordinary prices were paid for any consignment that made its way safely out of the South. In exchange for its cargoes of cotton, the Rob Roy would typically return to Texas with Enfield rifles, ammunition, blankets, shoes, and clothing, thus breathing new life into a strangling Confederacy. In addition to these necessities, Watson found it good policy to bring in such luxury goods as tea, coffee, cheese, spices, needles, and thread. Alcohol was legally forbidden but was ‘received with great thanks if given as donations for the use of the hospitals.’ [3]

Watson wrote in his second memoir (see below), ‘Blockade running was not regarded as either unlawful or dishonourable, but rather a bold and daring enterprise.’ Like his time as a Confederate soldier, Watson’s life as a blockade runner was also filled with excitement and danger. [3]

Despite generally being a most lucrative trade, Watson learned to his regret that blockade runners were ‘generally men more capable of contending with the seas and enemies than holding their own with shrewd and sometimes not over scrupulous men of business.’ Typical of the men who defied the Union fleet, Watson left blockade running no richer than he had entered it. Upon summing up the profits of the three voyages of the Rob Roy, Watson found that he had barely broken even. [3]

But it couldn’t have been that bad, as when William returned to Scotland in 1865, aged 37, initially to Glasgow, he was able to build a house at 127 Argyle Street, near St Enoch Square and start a ship building business in Greenock. In April 1871, he married Helen Milligan, the thirty-two-year-old daughter of a local baker. The witnesses to the wedding were his half-sister Jessie Watson, then 25, and his nephew Peter Watson, probably the son of William’s elder brother, John. [2] [4] [6] [7]

After the wedding, he built two houses in Skelmorlie which he named after his battles; Oakhill (Montgomerie Terrace) and Pea Ridge, now called Craigallion (also Montgomerie Terrace). These were completed by the time of the 1875 Valuation Roll, where he is listed as owner of both, albeit still with his main address in Argyle Street in Glasgow and he rented out Oakhill to a Mrs Helen E Anderson. [5] [6] [7] [8]

During this time, his business thrived. In 1878, he took over the Ladyburn Boiler works in Greenock and in August 1882, the Greenock Advertiser reported that Watson had launched the ‘Talisman’, a 160-ton iron screw steamer which was sold to a Glasgow fish merchant. [6]

Watson had learned a great deal about business practices from his time in America and when the construction of a railway line damaged his property, he sued and was awarded £22, 937 for prejudices to his business, the equivalent of over £1.5 m today. [6]

William Watson: The Adventures of a Blockade Runner; or, Trade in Time of War

In his retirement, William settled in Skelmorlie where he remained a trustee of the Parish Church. He wrote two books recording his adventures and giving his impressions of life in the southern states at his Pea Ridge villa. ‘Life in the Confederate Army: Being the Observations and Experiences of an Alien in the South during the American Civil War’, was published in 1887. This was followed in 1892 by ‘The Adventures of a Blockade Runner; or, Trade in Time of War. [1] [3] [5] [6] [9]

When ‘Life in the Confederate Army’ was first published, the Boston Sunday Herald proclaimed it ‘the best story of the Southern side yet written. It has been reserved for an unknown and comparatively unlettered writer—a British civil engineer—to furnish a better account of the condition of the South at the time of the secession, and a better sketch of life in the Confederate Army than has hitherto been written by anyone.’ [3]

William Watson: Life in the Confederate Army – American Civil War.

They went on to write that ‘In many ways, however, Watson was atypical of the citizens of the world who bore arms for the South. He wasn’t a professional soldier, nor a mercenary and he confessed that he “never was a very strong sympathizer with the South” and “was much opposed to the secession movement, and would have done anything I could to have prevented it.” Nevertheless, Watson’s service to the Confederacy was both loyal and courageous, and his year with the 3rd Louisiana Infantry, while uncommonly colourful, was also fraught with hardship and danger.’ [3]

Today William Watson, is remembered not for his actions during the war, but rather for his memoirs which have enlightened generations of Civil War historians. It has also been said that in Margaret Mitchell’s classic novel: ‘Gone with the Wind;’ Clark Gable’s character Rhett Butler, a Blockade Runner, was based on William Watson. [3] [6]

By 1895, William had built and was living in a new house, Beechgrove on Eglinton Terrace, possibly named after the final resting place in Tennessee of many confederate soldiers. He still owned Oakhill which he was renting to a Mrs Francis Ann Service or Spalding and Pea Ridge which he was renting to a Patrick Graham, Accountant. By 1905, he’d sold Oakhill but continued to rent out Pea Ridge, by that time to a George Bell Murray, Inspector R.N. He and family were still at Beechgrove. [1] [7] [8]

Watson died in 1906, just before his eightieth birthday. He was survived by his wife Helen and had had 3 children, Henry (1872) and Agnes (1875) and Mary (1876). [7]

References & Sources:

[1] Website: Wikipedia – en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Watson_(sergeant) and /Beechgrove

[2] Website: Skelmorlie Villas – www.skelmorlievillas.co.uk/people-of-local-interest/henry-watson-family/

[3] Website: Scots in the American Civil War – www.acwscots.co.uk/watson.htm

[4] Facebook: Celtic Confederates – www.facebook.com/ – https://www.facebook.com/546291228830523/posts/750277008431943/

[5] Book: ‘Skelmorlie: The Story of the Parish Consisting of Skelmorlie and Wemyss Bay’, Walter Smart, 1968.

[6] Website: Issuu – https://www.scribd.com/doc/1289541/Skelmorlie-Original-Walter-Smart-History-1968ssuu.com/jkeeman/docs/william_watson

[7] Documents: Birth, death and marriage certificates for William, Helen and Henry Watson

[8] Documents: Skelmorlie valuation rolls – 1875, 1885, 1895 and 1905 and 1881 Census.

[9] Book: Life in the Confederate army, being the observations and experiences of an alien in the South during the American Civil war. William Watson, 1888, Scribner & Welford, New York.