INTRODUCTION

BY WILMA MENHENNET DAVIDSON

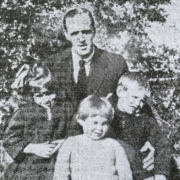

I first heard of the Skelmorlie Reservoir disaster from my father. When I was a child, he told me about how his 8-year-old sister and two boy cousins had died when the reservoir above the village burst its banks. At the time there were few details given, but a chance remark from another family member in later years encouraged me to investigate what really happened on that sad day.

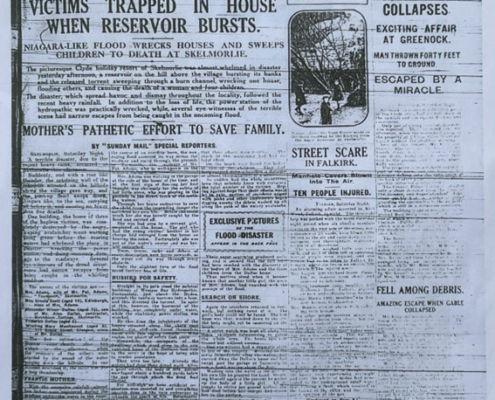

I now know that on Saturday 18 April, after days of torrential rain, the retaining wall of the reservoir above the village of Skelmorlie suddenly failed, and a torrent of water poured like Niagara” down through the village, which is built on a steep slope above the Clyde Estuary. Five and a half million gallons of water escaped from the reservoir in the space of ten minutes.

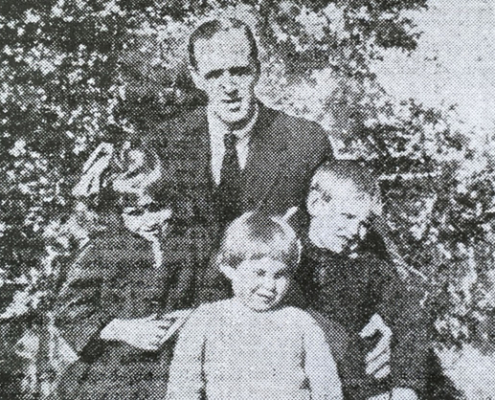

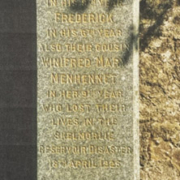

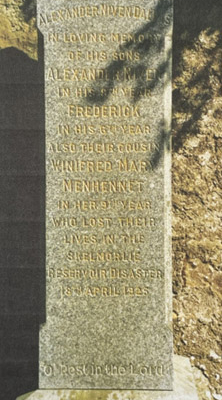

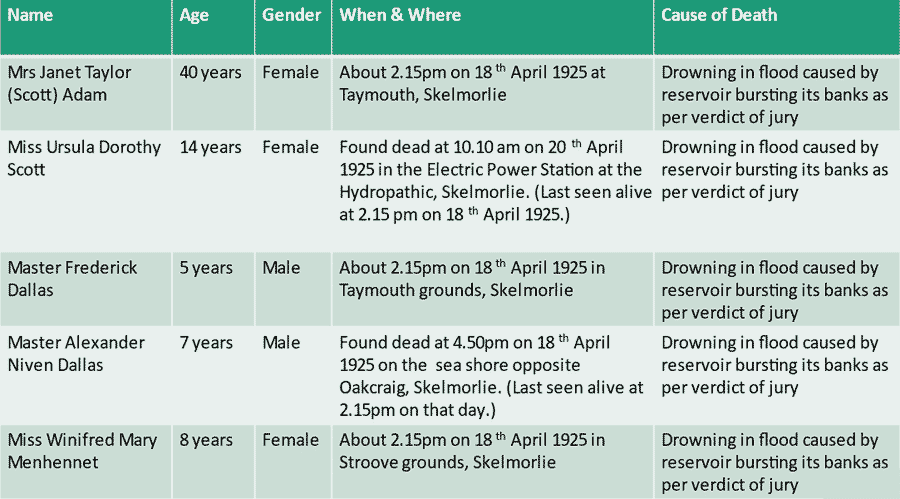

In all five people were killed by the flood waters, four of them children. Three died at Birchburn Cottage. They were Alexander Niven Dallas and his brother Frederick, along with their cousin Winnie Menhennet, who was on holiday staying with her aunt and uncle.

Across the road, and slightly downhill from Birchburn, a 40-year-old lady and her 14-year-old niece who was on holiday from Edinburgh were also killed.

This account is dedicated to the memory of the five people who lost their lives in the reservoir tragedy. It is a transcript of an article which appeared in the Scots Magazine in April 1996.

.

.

.

THE SKELMORLIE RESERVOIR DISASTER

By Wilma Davidson

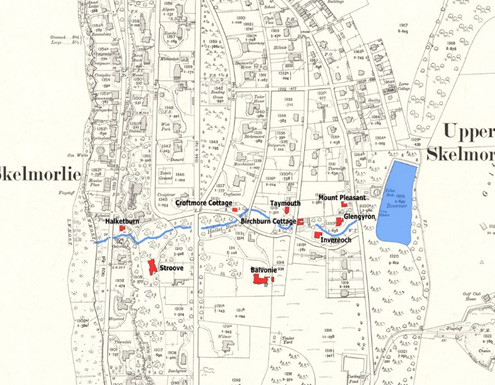

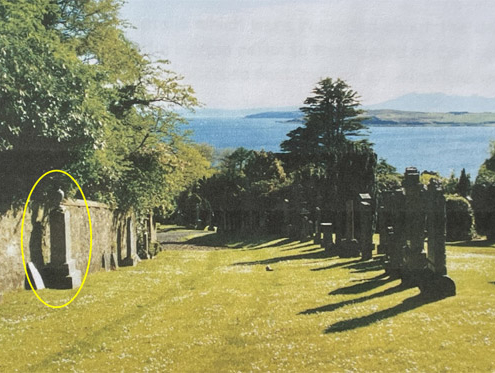

The disaster which struck the lovely Ayrshire village of Skelmorlie is almost forgotten today. You would hardly think to stroll around its quiet streets and leafy lanes that it had been the scene of such a tragedy. But if you look closer the scars are still there – the reconstructed garden walls, the gap site where a family home once stood, and the memories of some of the older inhabitants who remember the day a remorseless torrent tore down through the centre of the village, destroying everything in its track.

It happened on the 18th of April 1925, when a reservoir embankment above the town suddenly gave way, releasing millions of gallons of water down through the village. After ten minutes of sickening, deafening, devastating horror many homes, streets and gardens were shattered and five people, four of them children, lay dead.

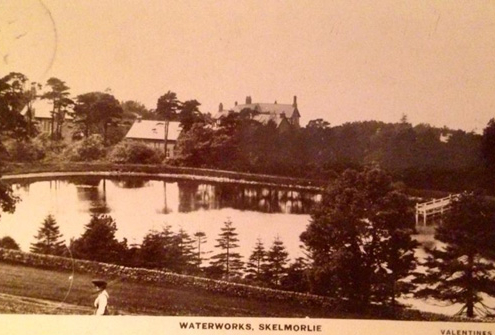

The reservoir, which belonged to the Eglinton Estate, provided the main water supply to the village of Skelmorlie. It had been built in 1861 by a local character known as Navvy Young, a sort of itinerant contractor, and his motley band of labourers. And it had been the subject of considerable apprehension for some time in the village because folk were aware it had received little maintenance since its construction.

These fears were compounded by the torrential rain and high winds which swept across the reservoir from the northeast on that fateful day.

Robert Donaldson, head forester and water superintendent of the Eglinton Estate, had carried out his routine check on the reservoir the previous evening, and again at 8.30 on the morning of the disaster. He found nothing particularly amiss but noted that only 3 inches of the 18-inch diameter overflow pipe was above the water level. It was extremely wet and stormy with a very high wind from the north. Spindrift was sweeping across the reservoir, depositing spray heavily on the bank. In the town itself residents remember the incessant torrential rain, the roads flooded, the misery of an Easter holiday ruined by typical west coast weather.

Meanwhile, a quarter of a mile below the reservoir in the yard of Birchburn Cottage, Sandy Dallas was preparing his horse and cart for that morning’s coal deliveries around the local farms and villages. His cottage was situated alongside the Halket Burn which served as an overflow from the reservoir. The burn descended steeply through a deep glen behind his property, flowing through his coal yard and alongside his cottage. The three railway men who were his lodgers had already left for their early morning shift at Wemyss Bay station. In the cottage were his wife Emily, his daughter and two wee sons, and their cousin Winifred aged 8.

Winnie Menhennet was on holiday from Glasgow. She was a frequent visitor, but on this occasion, she had been suffering from a bad bout of measles and had been sent to stay with her relatives in Skelmorlie in the hope that the fresh sea air would help to speed her recovery. She had been due to return home the previous day, but because the weather had been so awful, keeping the children indoors for much of their Easter holiday, the family decided that she should remain in Skelmorlie for a further week ….. a fateful decision.

Meanwhile, in Taymouth House, below the Dallas’s cottage, Patrick and Janet Adam were sitting down to breakfast with their guests, a niece and nephew from Edinburgh. Mr Adam was a brewer’s agent, his wife Janet (Jenny) a daughter of a well-known Clyde shipbuilder.

Further down the hill, in the plush Wemyss Bay Hydropathic, Skelmorlie’s famous and luxurious hotel, the staff were routinely preparing meals and services for the day, the residents breakfasting or lounging around talking, no doubt about the inclement weather which was keeping most of them indoors. Very few ventured outside to take the air.

No one could have suspected how unseen events further up the hillside would shatter their lives.

Skelmorlie endured the dreary boredom of a wet Saturday morning. In homes all over the village, breakfast dishes were cleared away, and children played indoors, watching the rain coursing down the windowpanes, and leaving deep muddy puddles all around. A few folk plodded through the torrential rain with shopping baskets. The morning wore on wearily, Sandy Dallas continued his round of deliveries. As the clock moved on families sat down to lunch. Wee Lizzie Dallas was sent to the shop for milk and eggs. She trudged out into the rain, complaining loudly.

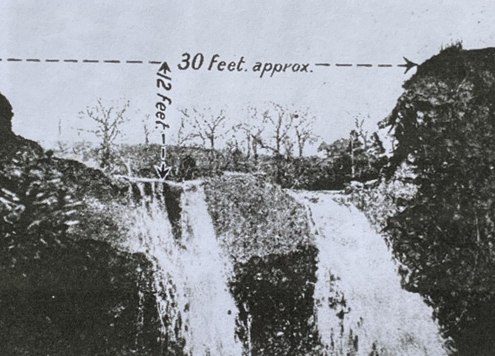

What happened next is etched forever in the hearts and minds of those who experienced it. Memories differ as to exactly when the disaster struck, but it seems to have been shortly after lunchtime. At around two o’clock a family living about fifty yards below the reservoir heard a loud crack and noted with alarm that two fissures had suddenly appeared in the embankment, and water was starting to seep out. A few seconds later the embankment gave way along a 30-foot length under the tremendous pressure of the water, and the flood suddenly surged with awful force down the steep slope on which the village is built.

One eyewitness said that the flood came down in a solid mass, another that it came in folds like the waves of a very angry sea. The wall of water was described as being about 30 feet high. People described a noise like thunder. Captain Scott of Stroove House said he heard “a roar, just a roar, like nothing else. Others said it was like the noise of a great motor car. One woman who saw the event from her window told the Greenock Telegraph that “the water was pouring out like Niagara”.

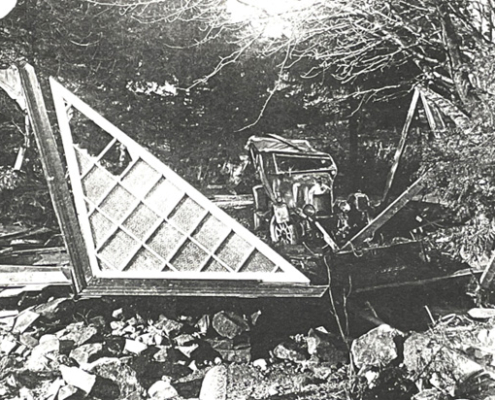

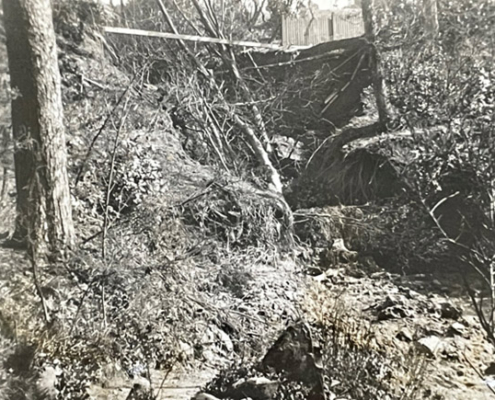

All obstacles in the way of the great torrent were torn up and carried before it, being deposited along the way or carried into the waters of the Clyde below. Trees, garden walls, outbuildings, rocks and roadways were all torn up in the relentless force of the flood. Wrecked motor cars and what was left of their garages were carried along in the torrent. Within ten or fifteen minutes the reservoir was almost empty.

At Birchburn Cottage, Emily Dallas heard the noise of the first escape of water, and rushed outside to see what was happening. She saw immediately that the overflow from the reservoir had suddenly and dramatically increased. She got the children outside, with the intention of warning the occupants of Taymouth House, slightly downhill from her own house, that water was escaping from the reservoir. She called on the children to follow her through the flood, but frozen with fear, they hesitated. At this moment a second great burst of water came thundering down with terrible force. She watched in horror, helpless as her home, and the three children were swept away.

James Robertson of Mount Pleasant had seen the avalanche of water strike the cottage and ran down through his garden to try to help. Sandy Dallas and a local farmer, John Paton, climbed onto the precarious corrugated iron roof of the stables behind the house, with the flood waters swirling around them, in an attempt to try to locate the missing children. All three men were soon wading waist deep in the fast-flowing water, endangering their own lives, but to no avail.

Emily Dallas’s cries had indeed alerted the occupants of Taymouth House. Jenny Adam was at the garage at the bottom of the garden with her nephew and niece and a maidservant. Alarmed, they decided to return to the house. The maid picked up the little boy and ran for safety. Jenny was quickly followed by her niece Ursula. But in making for the house the girl slipped and fell, and Jenny, without a thought for her own safety, turned back to help her. In that split second both were caught up in the flood which thundered into the garden and were swept away in its relentless grasp.

Patrick Adam was inside his house when the flood waters struck and managed to escape by climbing out of one of the ground floor windows. He was met by a distraught Sandy Dallas, who told him that the three children were missing. Patrick struggled down through his own garden to try to find out what had become of his wife and niece. Horror stricken, he caught a brief glimpse of Jenny in the flood waters, caught by a tree, before she was swallowed up in the raging torrent. There was no sign of Ursula.

The Hydropathic Hotel, which was situated on a high rocky cliff overlooking the main Largs to Greenock Road, suffered extensive damage. The waters thundered into the conservatory and flooded the entire basement to a depth of four feet, then poured out over the cliff face destroying the shore rood below. Some guests and members of the hotel staff were able to escape by ground floor windows. Warnings were shouted around the hotel, and thankfully all residents and staff escaped with their lives. But damage to the hotel was extensive, with furniture wrecked and expensive fittings and carpets ruined, and everything covered in thick mud and debris.

Skelmorlie’s electric power station, which was in the basement of the Hydropathic Hotel, was immediately put out of commission, with wreckage, boulders, and thick, filthy mud choking the machinery. The town instantly lost its electricity supply.

All down the hillside people had amazing escapes. A local gardener, James Murray, was climbing the Hydro steps beside Stroove when he saw the wall of water descending. He leapt into a tree and remained clutching at its branches until the danger hod passed. A family living at Croftmore Cottage succeeded in making for a hillock at the back of their house and remained there while the flood raged around them. A group of young men walking up the hill from the shore road were nearly engulfed in the flood but managed to run to safety. One of their number also escaped by climbing a tree. A charabanc full of passengers was almost swept into the Clyde by the torrent.

The occupants of the houses of Invereoch and Glengyron also had lucky escapes. Both houses had their gardens and lower floors extensively damaged, but the families were able to remain in the safety of their homes until the flood waters passed.

The house of Halketburn, on the main shore road, was directly in the track of the torrent, which divided itself around the house, making it into a temporary island. Mrs Campbell was used to the Halket Burn flowing past her home but was alarmed to see that the water was suddenly swirling wildly around her house, on both sides. She managed to get outside. When the flood eventually subsided the mess inside was indescribable, with heavy furniture scattered everywhere, and six inches of mud all over the ground floor. But her pet dog which had been left in the house was alive and well, having fortunately managed to get to an upper floor.

When the torrent had passed the scene in the village was one of utter devastation. A great chasm could be seen where the reservoir embankment had collapsed, trees and shrubbery were uprooted and strewn all over the place. Deep chasms were torn in the roadways at several places, and at one place just above Stroove House a hole in the road was gauged 12 feet wide and 40 feet deep:

Birchburn Cottage was completely demolished. What had been a happy family home only fifteen minutes before was now a shattered ruin, with not one wall remaining. Only the tiled grate remained standing in the centre of the cottage, and part of the stables at the back. The family’s furniture and belongings were scattered all down the hillside, describing the course of the torrent. Of the three children who had last been seen at the door of the cottage there was no sign.

The reservoir hod held three and a half million gallons of water. In a matter of ten to fifteen minutes it was empty.

A terrible silence descended on the village, as the shock of what had occurred gradually dawned.

As soon as the extent of the disaster was realised offers of help came from all quarters. Willing hands shifted debris and men waded waist deep in the muddy waters, in a desperate attempt to try to find anyone alive. But early optimism soon turned to sorrow, as the victims of the disaster were found one by one.

The first to be discovered was Jenny Adam, at the bottom of her own garden. A local joiner saw a hand appearing above the water and rushed in to pull her out. The onlookers thought they detected some small signs of life, and artificial respiration was attempted for almost two hours by Dr Hall, who was acting as a locum in the village, but without success.

Winifred Menhennet was found in the flood waters, caught on a bank, by Captain Scott of Stroove and the manager of the Hydropathic Hotel, Mr Campbell. They waded into the flood to retrieve the little girl. She was dead. Her skull had been fractured.

Wee Freddie Dallas, aged 5, was found dead a short distance from his home.

His brother Alex, aged 7.5, was carried half a mile right down to the shore and swept into the sea at high tide. His body was discovered only when the tide went out. He was half buried in the sand.

The search for the last victim, Ursula Scott of Edinburgh, was called off that evening as daylight faded, but resumed early on the Sunday morning. A party of fishermen were summoned from Largs on the Sunday to search the seabed with their sweep trawl, but despite working all day they were unsuccessful. There was so much debris from gardens and the shattered homes, masonry and trees on the seabed that their task was almost impossible. The search was again called off in the evening.

Local people organised themselves into work parties to clear the roadways, particularly the Largs to Greenock Road which was completely blocked for thirty yards. Men in plus fours, the local policemen and some drafted in from Greenock, all waded into the murky waters to remove racks and boulders and saw at tree stumps which were blocking the highway. They were joined by a party of footballers who had arrived that afternoon from Greenock, expecting to play a match in the village. Even some young ladies hitched up their skirts and joined in the effort.

The first news of the disaster reached the outside world at about three o’clock, when extra police officers from Greenock were summoned to Skelmorlie to assist the local force. Ambulances and medical staff were rushed to the scene. The news echoed around Cappielow Park during the match between Morton and Raith Rovers, as police messages were overheard by spectators. As a result, crowds soon started heading for Skelmorlie by every means of transport they could find – motor cars, charabancs, bicycles, and motorbikes, and many on foot.

The following day, by a strange quirk of fate, the rain stopped, and the sun unexpectedly shone on the scene of the disaster, bringing yet more crowds to gape at the stricken village. They watched as the fishermen trawled for the body of the missing girl and had to be kept back by a strong police presence from those properties which had been worst affected.

It was on the Monday morning that Ursula was found by chance by an electrician who went into a storeroom of the electric power station, in the basement of the Hydropathic Hotel. Because it was dark, he struck a match to inspect the damage, and saw the body of the girl lying in the far corner, half buried in the mud and debris which had been swept down the hillside.

A Public Enquiry into the disaster was held at Kilmarnock on 15 June 1925. Evidence was heard from the local police inspector who had directed the rescue operations, and from various civil engineers and other experts.

So how did it happen?

The reservoir which served the village covered about 21- acres. With a capacity of nearly 5.4 million gallons it was in fact really only a tank for gathering water from an upper reservoir.

The upper reservoir had a system of sluices and culverts to carry away excess water. Robert Donaldson, the water superintendent for the Eglinton Estate, in his evidence to the inquiry, stated that the 12” overflow pipe at the upper reservoir was choked with sand or silt, and had been for some eight weeks, a fact which he hadn’t previously thought to be of any significance.

In addition, he said that the Beithglass Quarry below the upper reservoir, which usually held a considerable quantity of water, was empty on the Sunday morning following the disaster. This had previously happened in 1911, and he assumed from this that another sudden rush of water from the quarry caused the disaster.

Inspector Beaton, of the Largs Police, said that he visited the upper reservoir just after the disaster. He said there were two overflow pipes there, one at the Kelly Burn and one at the Beithglass Quarry. The 12″ pipe at the Kelly Burn was half choked with sand or silt. He said that the quarry was empty, although there was usually a considerable amount of water in it. It was 20 feet deep at its deepest part, and the water seemed to be getting away, presumably through some underground culvert since there was no obvious route for the water visible above ground.

Mr Hogg, Civil Engineer, said in his evidence that “The proximate cause of the failure was the inadequacy of the overflow arrangements. The 18” pipe was not a proper provision, and especially the freeboard of 1.25 feet was grossly insufficient’.

So, the disaster was caused by a combination of circumstances – the inadequacy of the overflow arrangements, lack of proper supervision and maintenance, the abnormal rainfall of the previous few days, which severely taxed the capacity of the reservoir and the sudden release of water from the Beithglass Quarry which had proved too much for the embankment to bear.

Questions were asked in parliament and considerable debate raged for some time about the blame for the reservoir disaster at Skelmorlie, but it was only when a further dam burst at Dolgarrog in Wales in November of the same year, causing further loss of life, that the government of the day considered that legislation governing the safety of reservoirs was required. This resulted in the Reservoirs (Safety Provisions) Act of 1930.

Lizzie Dallas survived the disaster which killed Winnie and her two brothers only because she had been sent to the shops and was away from the house when the flood occurred.

Although I was told the story by my parents, it was Lizzie (or Betty as I knew her) whose personal and very moving account of the tragedy prompted me to investigate the circumstances in more detail. She was my father’s cousin and Winnie Menhennet was my father’s sister.

Wilma Menhennet Davidson